By Warren Thomas

In the Sept. 9, 2013 edition of the Sanborn Weekly Journal, Dvonne Hansen reminisced about her days in a one-room country school. Her experiences in Forbes School Union No. 1 mirror my own in remarkably similar fashion. I’m not sure of her later-than-my-years, but my treks to Floyd No. 2 and then Floyd No. 3 began in 1935 and ended in 1942. (Surely does date a guy, doesn’t it?!)

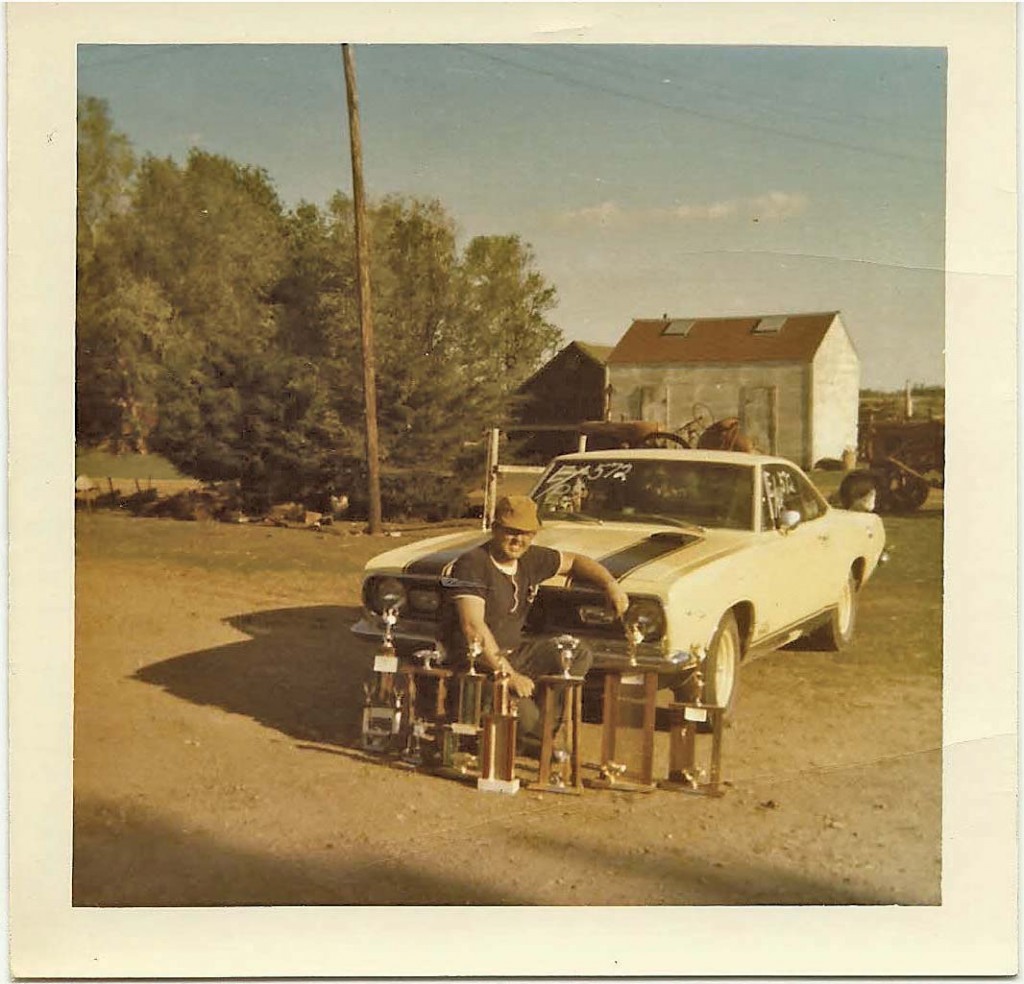

ABANDONED ONE-ROOM schoolhouses, such as this Harmony Hall school northeast of Forestburg, are a monumental reminder of rural prairie history.

I quote from her last paragraph, “As enrollment dropped, schools were reorganized and shipped to larger schools.” Few will know or remember of what that reorganization consisted. Understanding the education evolution of Sanborn County schools in the past 60 years is to recall Senate Bill 6 and its far-reaching effects from about 1954 and later.

With the passage into law of Senate Bill 6 came the mandate to place all the state’s rural schools in one of the independent (town) districts, thus eliminating the common (rural) school districts. The net effect was the grass roots, homegrown local control of their nearby schools would be transferred to one of the four more distant town schools. Such perceived loss of local control produced fear, fighting and factions.

Implementation of the restructuring lay in the laps of seven elected members of the newly-created Sanborn County (and all other counties) Board of Education. One member was elected on a non-political ballot from each commissioner district and two at large. Original members were Tom Brisbine, August Kundert, Robert Unterbrunner, Katherine Senska, Omer Fouberg and Wilma Thomas (older readers – help me out with the seventh). Edna Titus, county superintendent of rural schools, became the secretary and Gerry Bollinger, states attorney, was legal advisor. When my father died in 1958, my mother resigned and I was appointed to replace her. After two years, the board elected me their chairman, a position they asked me to fill the last 10 years of that board’s existence. Later Board replacements were Merlin VanWalleghan and Chuck Graves. As far as I know, Merlin and I are the yet-living members.

I am interested in providing this historical data, much as Dvonne has done, because I know of no other record showing what triggered the demise of our country schools — at least in any detail.

For the moment back to the educational set-up in Sanborn County prior to Senate Bill 6. Four town elementary and high schools had evolved in our county with stories all their own. Throughout the state, laws provided that elsewhere rural schools were to be established. To these approximately 64 Sanborn one-room buildings parents sent their farm children who usually walked up to one or two miles. Three neighborhood farmers or their wives formed each of the school boards who hired their teachers, provided coal for the pot-bellied stove, repaired roofs and windows, extracted skunks from beneath the building and other less exciting responsibilities.

To modern minds, it may be quite a stretch to visualize approximately 64 widely scattered one-room buildings in a county just 24 miles square. Within were 16 townships, each, according to according to Sanborn County Clerk of Courts Susan Johannsen, with at least four schools, if not five. Imagine — at least 192, and perhaps 240 farmers serving their local schools and hiring annually from 64 to 80 teachers, depending upon the exact number of schools!

Teachers were paid from $40 to $75 a month and usually “boarded round,” meaning they stayed on a rotating basis with various families whose children were in their school. Many teachers walked, carrying lesson plans and lunch. Students did the same, although some rode ponies or horses. A few teachers drove cars.

Someone has said that nothing is as certain as change. I continue with how some of that change occurred in Sanborn County.

In 1955 or 1956, our county school board began the arduous task of holding patron meetings throughout the county. I recall that we began in Ravenna and Diana townships. As we proceeded we tried to discern into which town (independent) district various landowners wanted their land, and therefore their students to go. Certain state laws regarding adjoining and contiguous boundaries dictated what the board could or couldn’t permit. As much as possible, we tried to put all of a landowner’s adjoining acres in a single independent school district, thus providing a single tax levy for school purposes on his land. The term “landowner” carried considerable significance. Landowners pay taxes; taxes operate local schools, thus receiving primary attention of the county board. Renters received little consideration because, owning no land, they might have been “here today and gone tomorrow.”

The job was not easy; change was hard. To many, the closeness of neighborhood relationships was being violated. Some could not readily accept that times were changing. The county board was often looked upon with aggrieved suspicion, even though we were neighbors and friends to people throughout the county. On one occasion a German-accented farmer in bib overalls stood to his feet and with considerable feeling declared, “The one-room school was good enough for me and it’s good enough for my kids!”

At a meeting in the Artesian High School study hall, I had to tell one landowner to return to his seat or I would call off the meeting. He came charging up the aisle, fists ready, to openly challenge a neighbor with whom he seriously disagreed over where the boundary line should be drawn.

Disputes arose, not so much with the board itself, but because of its proposed Forestburg/Woonsocket boundary lines with participants harking back to pioneer days when Woonsocket “stole” the county seat records from Forestburg. One group was highly incensed when a school superintendent, just a hired employee in his district and paying no property taxes, openly championed closing rural schools.

Sometimes hostilities arose over desired boundary lines simply because of long-standing disagreements between landowners. Some thought their taxes would increase if they were forced into a larger town school district. Others were more comfortable with that which they had always known.

But in all our decisions, we were careful to consider where the citizens wanted their land and their children to go. However, that kind of neighborly consideration led to our drawing amazingly angular district lines between the four independent districts. For that, we were criticized. However, when we were taken to court two or three times by aggrieved taxpayers over boundary lines, we were repeatedly exonerated by court decisions. Each time our actions were upheld because we were considered to have acted with “reason and prudence”in difficult and tumultuous situations. Even the South Dakota Supreme Court ruled in our favor.

We did what we had to do — carry out the law. I remember them all; the voters had chosen wisely: Katherine, Robert, August, Tom, Omer, Merlin, Chuck and my mother, Wilma, before my time. Each was steady, dependable and supportive of public education. After some 12 or 14 years, all the Sanborn County rural schools were incorporated into the independent districts and shortly were closed. Senate Bill 6 met its legal phasing out.

Diminutive Edna Titus, once my Floyd 3 fifth and sixth grade teacher, was our constant, capable, efficient secretary. I have wondered about her unspoken feelings. The many rural schools to which she had given years of oversight as county superintendent of schools were now being eliminated right before her eyes. She never questioned the board’s decisions. She knew the law.

States Attorney Gerry Bollinger, always giving deference to the will of the county board, was a stalwart and dependable legal advisor. We valued him as an indispensible team member, especially when he prepared our defenses in various courts of law.

Few one-room school buildings remain on their original sites. The only one of which I am aware is Floyd No. 3, a mile across the field from my house. Windowpanes are missing, the roof leaks and raccoons, mice and skunks replace the Stuart Pearson, Freddie Wormstadt, John Hanson and Les Thomas children, who began their education there. The one-room school era has passed.

Warren Thomas,

Forestburg

wlthomas@santel.net